|

PRE AND PROTOHISTORY In 1981, the paleo-anthropologists and the paleo-biologists put the appearance of the oldest australopithecus at 7 or 8 million years ago. In 1983, scholars present the role of Eastern and Southern Africa as the presumed cradle of the first hominids To learn more, click here (annexe 1) Homo sapiens appears between 200 000 and 150 000 years before our era and modern man, Homo sapiens sapiens, around 35 000 BC. THE PALEOLITHIC

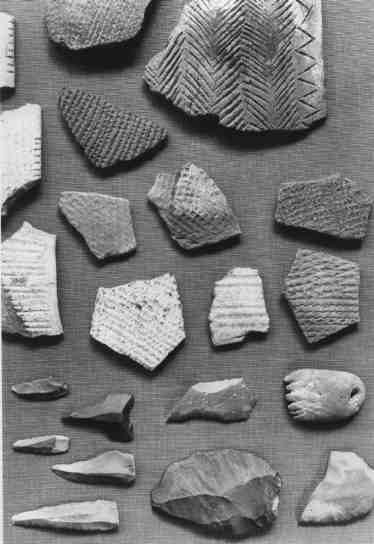

The Nile Valley is inhabited since ancient times. 800 000 years before our era, they leave traces of tools in the form of coarsely cut pebbles (with one or two flakes) near the Third Cataract. In the same context were found animal bones belonging to species that today have disappeared. During this period, the lithic material appears in the form of a basic hand axe. Some specimens are found at Khor Abu Anga, at the junction of the White and Blue Niles, and are dated to between 500 000 and 300 000 years BC (corresponding to the Acheulian, or lower Paleolithic). However, in chronological terms, these tools are related to the following period, the Middle Palaeolithic. Pre-historians, among them Jacques Reinold, have concluded that this was a special enclave that extended to Nubia, and as far as Khartoum and towards the Red Sea, where more developed populations benefited from a more favourable environment. This culture is characterised by bifaces.

Around 70 000 BC a climate change heralds the Middle Paleolithic. Torrential rains favour the production of food resources and the appearance of a new technology. The tool is planned, its cut predetermined and worked by a method called the Levallois, with percussion platforms prepared around the object. In Nubia, this episode is related to the Mousterian, an industry identified in the south of France. The corridor of the Nile is enriched by variants with bifaces, points and scrapers, making one think of a development specific to this area. The discoveries on the island of Saï have revealed tools of quartz and a rare specimen of a mortar, dated to c. 200 000 BC, which could prove Francis Geus thesis “on the dispersion of modern man in East Africa”. |

Prehistorical scarved stones and ceramic fragments probably made at neolithic period. / Outillage lithique et tessons de céramique probablement élaborés au néolithique

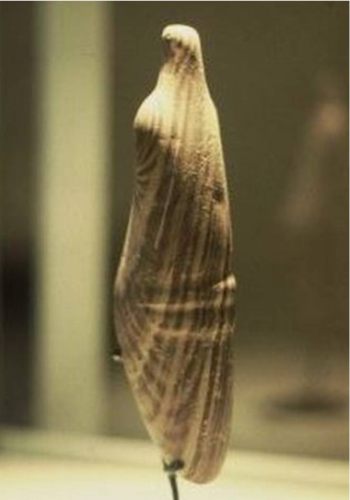

Sandstone statuette digged out of neolithic graves usually of important persons, probably made in a pebble of river. Joy Soulé-Nan found a similar pebble in the Ouaddi Mathendous (Fezzan-Libye) after some strong rains. Very pure style / Statuette de grès lité excavée de tombes de personnages importants (période du néolithique) et probablement élaborée à partir d'un galet de rivière. Joy Soulé-Nan a trouvé un galet similaire dans le Ouaddi du Mathendous (Fezzan-Libye) après de fortes pluies - Style très épuré

Statuette from a group A culture grave, with some tattooing on the hips and thighs. The head like a stick reminds some rock paintings in Central Sahara / Figurine féminine d'une tombe de la culture du groupe A. Tatouages au niveau des hanches et des cuisses. La tête de type "batonnet" rappelle quelques peintures rupestres du Sahara central

Group A burial (photo Rex Keating during the Unesco campaign 1960-1968) / Inhumation d'un défunt du groupe A (Photo Rex Keating durant la campagne de l'Unesco 1960-1968)

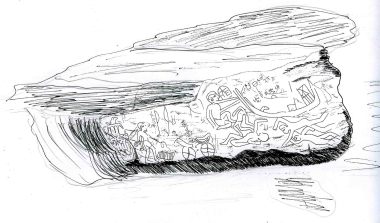

Fighting scene on the stone Cheikh Suleiman against group A (Second cataract - 4100-2800 BC) See illustration on next picture / Scène d'affrontement sur le rocher du Cheikh Suleiman contre le groupe A (Seconde cataracte - 4100 - 2800 avant notre ère) Voir illustration sur photo suivante

Illustration from the "Nubie des pyramides", written by Joy Soulé-Nan / Illustration extraite de la "Nubie des Pyramides" de Joy Soulé-Nan

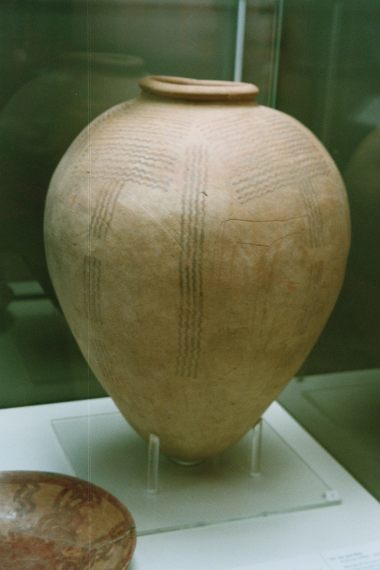

Group A ceramic pot from Aksha cemetery probably imported from Egypt to Nubia (4100-2800 before Christ) / Jarre en céramique du groupe A (4100-2800 avant notre ère) problablement importée d'Egypte en Nubie

Nubian historical periods (Francis Geus) / Grandes périodes de l'histoire de la Nubie (Francis Geus)

|

|

The upper Palaeolithic (35 000 - 12 000 BC) is climatically a dry period, which pushes the populations towards the river banks. Technology adapts to this new environment and the tools develop towards microliths. This industry highlights several well adapted small groups of humans that generate important cultural sequences. To learn more, click here (annexe 2) The majority of the populations seem to have been hunters-fishermen-gatherers. In the final Palaeolithic the Nile appears to settle into its current course, with the confluence of the White and Blue Niles at Khartoum. Some sites stand out during this period: Argin between the First and Second Cataracts, Jebel Sahaba near the Second, Saï downriver from the Third, Khor Abu Anga to the north-west of Khartoum, Khasm el-Girba on the Atbara and Singa on the right bank of the Blue Nile.

THE EPIPALAEOLITHIC This terminology, copied from that used in Europe, dates to around 13 500 and 10 000 BC, albeit with a different chronology and climatic conditions. Heavy floods increased the surface of the alluvial plain and, after the disappearance of the waters, the production of food became a major occupation. The hunting of the larger mammals, fishing, collecting fresh water molluscs and the gathering of wild grains contributed to technological development. Grinders appear, and the microlith industry is at its peak. The Nile corridor is characterised by a cultural diversity that demonstrates its excellent adaptation to the environment. Four industries emerge. To learn more, click here (annexe 3) THE MESOLITHIC This period dates to around 10 000 BC and concerns Upper Nubia as far south as Khartoum. The Last Great Pluvial Period sees the return of the steppes and an inviting savannah for the nomads and semi-nomads. This environment favours the appearance of the first receptacles in fired clay for the storage of grains or other food stuffs. Elsewhere in Africa, they are already present in the middle of the IX millennium. To lear more, click here (annexe 4) It is during this period that domestication gives significant resources to the local populations, together with the resources from hunting, among which fishing plays an important role. The 'Khartoum Mesolithic' covers two and a half millennia (between 8500 and 6000 BC), laying the foundation for the famous 'Neolithic revolution' where Nubia serves as a particularly good case in point. Excavations have revealed sites located at the confluence of the White and Blue Niles (at Khartoum), upriver from the Sixth Cataract (at Saggai) and on the right bank of the Nile in the Butana plain (at Shaqadud). During this period, the centre of Africa undergoes an extreme tropical phase, where the Last Great Pluvial Period (between 10 000 and 5 500 BC) installs a watery barrier from the shores of the Atlantic to the horn of Africa. To learn more, click here (annexe 5) THE NUBIAN NEOLITHIC This period begins in the V millennium, and reached its peak around 4 500 BC. Its end came at the beginning of the second millennium of our era. The Neolithic is the result of a continuous evolution where man adapted to his new environment. His living conditions allowed him to apply a new way of thinking, giving up the essentially predatory activities in favour of a productive society. After hundreds and hundreds of thousands of years, characterised by an evolution based on stone tools, the Neolithic, described as 'revolutionary' by Gordon Childe, sees changes in the spheres of economy, politics and religion. The way of life and social relations evolve. The climate becomes drier. Human groups move closer to the sources of water and settle on the alluvial plains.

To learn more, click here (annexe 6) The beginning of desertification generates, around the 22nd parallel north, two different economic worlds: the populations of Lower Nubia and central Sudan devote themselves principally to pastoralism. In general, agriculture associated with animal husbandry contributes to the demographic development and the drying out of the savannas influences human settlement patterns. The first villages appear and function thanks to a chief, whose power is attested by his funerary goods (objects and food stuffs deposited during the funeral, for his use in the afterlife). To learn more, click here (annexe 7) The person of the king, an intermediary between the visible world and the forces of nature, without doubt had a magic-religious role. He had to ensure that his group integrated within its environment and guarantee its survival and security. The supply of food, especially when hunting was practiced, brought together the concepts of prosperity and fertility that went beyond the simple role of chief. After his death, he maintained his status, becoming the central focus of the world of the ancestors.

To learn more, click here (annexe 8) The funerary goods have both cultural and cult significance. The omnipresent finery speaks of the personality of the dead person, who most likely believed they had protective powers. They imply a belief in an afterlife. Since the Neolithic, pottery becomes important, and over a thousand years can be seen to have different characteristics in different areas. It's an explosion of forms and decorations with bowls, cups, dishes, bottles and large storage jars, of the ‘granary’ type. Also worthy of mention are the beautiful caliciform beakers found in some burials, that the sites of Kadero, Kadruka and el-Kadada have allowed us to study. Female statuettes are also associated with the world of the dead, in particular those placed next to the deceased. In Upper Nubia, they divide into two categories: those that present a feminine morphology and those whose silhouette is merely suggested, like the statuettes made of variegated sandstone that possess such a power of suggestion, that one seems to be in the presence of an entity. It is possible that the material was found in the wadi beds sculpted by the river's current. This type of 'raw' find has been discovered in the Libyan Sahara, in the ancient river of the Mattendush. In the funerary world, animal offerings played an important role. Bucrania were excavated in some burials. Dogs and goats have been found, but sheep seems to have had a particular significance in the late Neolithic. For this subject, consult "La Nubie des Pyramides"

ROCK ART During the Neolithic, the paintings and engravings on rocks decorated the sides of the African jebels and wadis . Today, the Sahara reveals itself a veritable open air museum, uniting the decoration and themes that are on view at the exceptional sites. The main sites are located in Algeria, in the Saharan Atlas and the Wadi Jerat in the Tassili-n-Ajjer. They are in the Tadrart Acacus massif, the Wadi Mattendush, and the Messak Settafet in Libya. They join Jadu in Niger, the West Tibesti and the Ennedi in Chad, and Sudan, not excluding the Nile valley. They give us information about the environment of the pastoralists-hunters-gatherers. Some artists have expressed rituals and beliefs where the animal world is honoured, associated to the human world where life and survival depend on this environment.

To learn more, click here (annexe 9) From the Atlantic to the Red Sea, thousands of cattle were engraved. They testify to an extensive pastoral culture and suggest a progressive degree of domestication. The animals that are not considered dangerous are domesticated, beginning with the youngest. Engravings show antelope, gazelle and cattle with tethering stones, necklaces, pendants and lassos. After the Last Great Pluvial Period, the retreating waters left behind islands and newly exposed parts of the mainland, creating an environment propitious to the domestication of wild or half wild ruminants. The great black ox called auroch inhabited the Nile Valley since the most ancient times. In the Pre-dynastic period, Egyptians attempted to capture these animals, so as to be able to make offerings of meat to the dead. Rock art is a fascinating 'book', that tells us about the daily life of men. The populations, anchored in their environment, believed in the specific forces of the animals. The whole Nile valley, and the egyptian world in particular, knew how to illustrate by analogy and symbol the forces of nature and the universe through this animal world. A rock carving at Youf Haket in the Algerian Sahara (Hoggar) depicts a bovine, face on, surmounted by a 'Hathor' symbol with a cow's head. This carving, that has a patina dating to before the V millennium, opens the question of a possible Saharan origin of the iconography of the egyptian goddess Hathor.

AT THE ROOTS OF THE GREAT STATES According to Jean Vercoutter, from the end of the V Millennium until the middle of the IV millennium, all happens as if 'a single and unique civilisation had reigned over Upper Egypt from Asyut to Jebel Silsileh, where began the future T3-sty (the South)'. The end of the rains between 5500 and 4800 before our era allowed the populations to busy themselves with the fluvial terraces, the golden age of small communities. Towards the end of the IV millennium, the desertification above the 22nd parallel confined the populations of Egypt and Lower Nubia within the Nile corridor, while the Middle Nile and central Sudan benefited from fertile zones in the basins of Abri-Delgo, Dongola, Shendi and the Butana.

To learn more, click here (annexe 10) However, pre- and proto-dynastic Egypt is characterised by a culture called the Badarian (V millennium before our era). It appeared to the south to Asyut in Middle Egypt and presents similarities with the Neolithic of the 'Land of Cataracts'.

To learn more, click here (annexe 11) In the middle of the IV millennium, a group of communities formed proto-states (Gerzean period) and the first settlements appeared at Abydos, Coptos and Hierakonpolis. The demographic development seems to be tied to sedentarisation. One observes a rapid evolution of the social institutions: writing and the conventions of drawing gradually become structured. At the end of the IV millennium, the unification of Egypt is a dramatic development. No longer are there confederations, but a single power put in place through undoubtedly dramatic events. The ceremonial palette of Narmer, seems to be part of this series of events. In the 'Historical Annals', this king figures as the first human ruler who apparently founded the town of Memphis, although he was not the unifier of Upper and Lower Egypt. THE A-GROUP, A NEOLITHIC POPULATION OF LOWER NUBIA (c. 3 500 - 2800 BC) Located between the First and Second Cataracts, Lower Nubia was always a sensitive area: southern border for the North (Egypt) and northern for the South (Nubia). Populations develop there since the Badarian period between Kubaniah, to the north of the First Cataract, and Dakka, at 150 km further south. Throughout its development, the A-Group enlarges its sphere of influence beyond the Batn el-Haggar. At the end of the IV millennium, the populations give themselves over to trade, through which raw products of African origin and manufactured ones from Egypt give this group a key position that will occasion its demise.

To learn more, click here (annexe 12) Egypt moves into Lower Nubia as far as Batn el-Haggar. The Palermo Stone mentions that an expedition of the king Snefru (IV Dynasty) took 7000 prisoners and 200 000 heads of cattle there. If these numbers are not absolutely accurate, this episode nevertheless sounds the death knell of the A-Group populations. The exploitation of this territory by the North continued until the fall of the Egyptian Old Kingdom (c.2160 BC), a fall undoubtedly caused by a boomerang effect. One may wonder at the fact that the army, the police and the praetorian guard of the egyptian king, were essentially made up of nubian mercenaries, according to the king Djoser. Did they defeat a regime that they held responsible for the extermination of populations close to their own ethnic group? On the fall of the Old Kingdom Egypt entered a period called Intermediary; there is no central power, which allowed the South to regroup and reorganise.

On this subject, consult "La Nubie des Pyramides"

|

|