|

THE KINDOMS OF NAPATA AND MEROE In Upper and Lower Nubia, the Napatan and Meroitic episodes begin at the end of the reign of Tanwetamani (656 BC) and end around the IV Century. After this, a post-Meroitic period gives way to a new order, that of the Christian world.

The geographic position of the Land of the Cataracts allows Nubia to remain on the sidelines when turbulence hits the Near and Middle East: during the first half of the V Century BC, the Median wars oppose the Greeks against the Persians, while in Egypt, the Persian invasion precedes the domination of the Ptolemies. At the crossroads of the commercial routes of the Mediterranean world and, of Sub-Saharan Africa, the kingdoms of Napata and Meroe regain the monopoly over the exchanges. The town of Alexandria and the emporia of Tripolitania are the main beneficiaries; it is through the Hellenistic world and then the Roman that the two kingdoms will enter 'modernity'. Without denying the Egyptian achievement, the kingdoms of Napata and Meroe retrieve ancient local traditions, reasserting their own beliefs. The human component, based on the same ethnical identity, reinforces their roots, thanks to a language descended from the proto-Meroitic of Kerma. The introduction of 'indigenous' elements develops two historical phases: the kingdom of Napata (from 656 to c. 300 BC) and that of Meroe whose extinction as a state occurred in the IV Century AD, following the military campaigns of the kingdom of Axum, in present-day Ethiopia.

THE KINGDOM OF NAPATA The successors of Tanwetamani: Atlanersa, Senkamanisken and Anlamani (656 to 593 BC) made Napata, located near the Fourth Cataract, the capital of the kingdom. It is likely that the latter sovereigns had the intention of re-conquering Egypt because among their titles they retained the title 'King of Upper and Lower Egypt'. As for the sphinx of Senkamanisken (643-623 BC), he always wears the pschent, the royal headdress characterising the union of the Two Lands. |

Pyramids from Nuri's cemetery / Les pyramides de la nécropole de Nuri

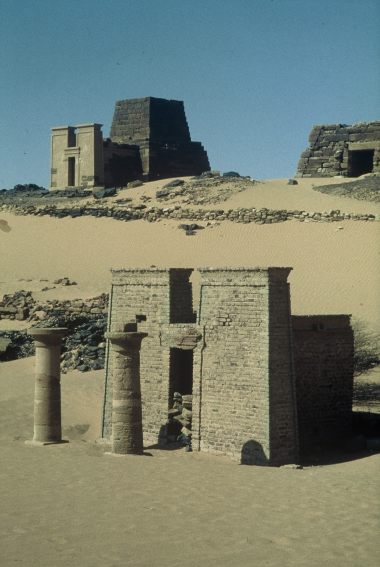

Vestiges of Amon's Temple in the royal city of Méroé / Vestiges du temple d'Amon de la ville royale de Méroé

Vestiges of the Sun Temple, situated not far away of the old royal city of Meroe / Vestiges du temple du Soleil situé à proximité de l'ancienne ville royale de Méroé

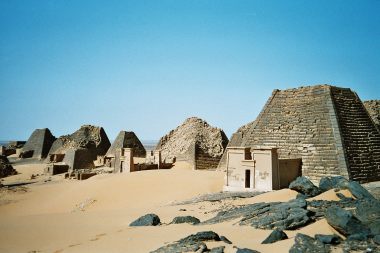

Some pyramids at the northern cemetery of Meroe / Pyramides de la nécropole nord de Méroé

Northern cemetery of Meroe / Nécropole nord de Méroé

One of the temples of the great enclosure at Mussawwarat / Un des sanctuaires de la grande enceinte à Mussawwarat

Lion Temple of Apédémak at Mussawwarat / Temple du dieu Lion Apédémak à Mussawwarat

Amon's temple at Naga / Temple du dieu Amon à Naga

Rams alley before the temple of Amon at Naga / Dromos de béliers précédant l'entrée du temple d'Amon à Naga

Side view of the Amon's temple at Naga / Vue latérale du temple d'Amon à Naga

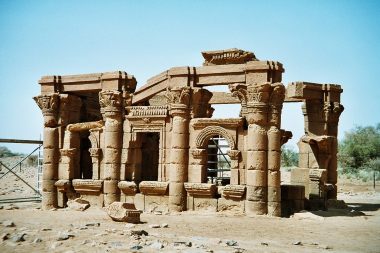

Greco-roman kiosk at Naga / Kiosque gréco-romain à Naga

Lion temple of Apedemak at Naga / temple du lion d'Apédémak à Naga

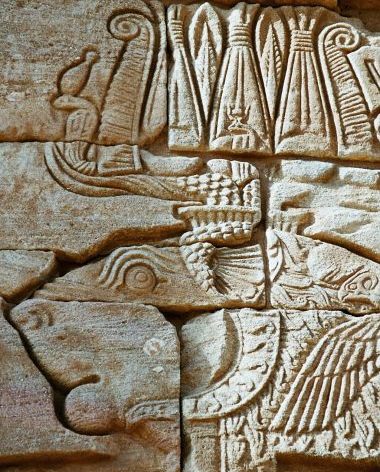

At Naga, on one wall of his temple, the lion god Apedemak wears the atef crown. He is protected by the god Horus. The ram horn of the god Amon ornaments his ear / A Naga, sur un des murs de son temple, le dieu lion Apédémak porte la couronne atef. Il est protégé par le dieu Horus. La corne de bélier du dieu Amon orne son oreille

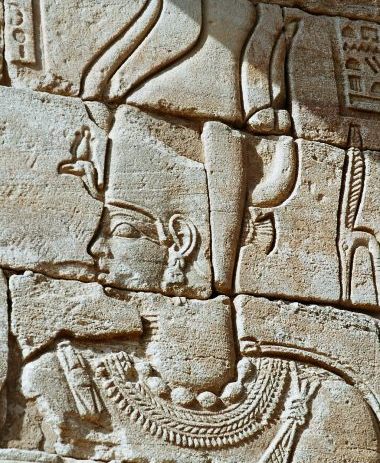

At Naga, on the lion temple of Apedemak, bas-relief of Satis deity belonging to the triad of the First cataract. She wears on her head a vulture skin and the antelope horns / A Naga, sur le temple du dieu lion Apédémak, représentation de la déesse Satis de la triade de la Première cataracte. Elle porte sur la tête la dépouille de vautour et les cornes d'antilope

|

|

The move of the capital to Meroe at the end of the reign of Anlamani was caused by the raid of the Egyptian king Psammetic II but also by the increasing desertification around Napata. The Election Stelae of his successor, Aspelta, confirms this transfer, but his accession to the throne suggests dynastic problems.

The stelae written by the sovereigns, in the best Egyptian tradition, mention the edification of pious foundations and offerings made to the gods. The military campaigns are also consigned to the Annals. The royal genealogy, that stretches over three and a half centuries, nevertheless remains imprecise. The most significant kings are Anlamani, Irike-Amanote, Harsiyotf and Nastasen. The wife of Nastasen, Sakhmakh, rose to the throne and received the name of Horus together with the title of Kandake, a title reserved for the sovereigns that had governed the country, like Nasalsa, mother of the king Aspelta.

THE KINGDOM OF MEROE This kingdom had an important impact on the imagination of the ancient authors. To learn more, click here (annexe 2)

'The Island of Meroe' includes the capital and its harbour, Wad Ben Naga, as well as holy towns, including Musawwarat es-Sufra. An urban network completed these settlements with Basa, el-Hassa, Hosh Ben Naga, Jebel Geili, Khartoum and Soba. In the current state of research, it is difficult to understand the exact chronology of the kings, our understanding of the reigns often being limited to the mere mention of kings and queens, carved on the walls of the pyramid chapels or on the offering tables. Furthermore, the understanding of Meroitic writing has not yet brought enough light on the history of this period. However, there are three characters that appear in the reliefs of the temples or in the official inscriptions. It is the qore, the kandake (or Candace) and a man bearing the title of pqr. Of profane architecture, there only remain the traces of palaces and fortresses and the location of some hafirs. The palaces were economic units that collected and distributed the products of a non-monetary economy, including the merchandises of the Mediterranean basin. These edifices were connected to the religious domain, and it is likely to have been the case of the palaces of the queen Amanishaketo at Wad Ben Naga and of the king Natakamani at Jebel Barkal. The sovereigns and the royal family were at the heart of the funerary traditions, but in the II Century AD simplified rituals give to individuals a liturgy that guarantees eternity. The cemeteries of Meroe illustrate the apogee of the kingdom. Today a visitor will still be impressed by the number of monuments, some forty of which are pyramids. A better knowledge of these buildings has been possible thanks to restoration campaigns begun in 1976 and directed by Friedrich W. Hinkel, a great architect as well as Nubiologist. To learn more, click here (annexe 3)

It should not be forgotten that there were local deities that receive a national cult together with the gods Apedemak, Sebiumeker 'lord of Mussawarat', Arsenuphis, Mandulis and Khaskhas whose temples take on a simplified plan, that is to say one or two rooms with a colonnade, preceded by a pylon of Egyptian type. As for writing, the kingdom of Meroe has its own alphabet around the II Century BC. For a century, linguists have tried to decode a language that can be read but is still not understood. The pioneer was the British Egyptologist Francis Llewellyn Griffiths, who in 1911 published two volumes of Meroitic Inscriptions in Expedition to Nubia, where the meaning of some words was suggested. This brilliant researcher made a surprising discovery: that the Meroitic signs are turned the opposite way to those of Egyptian writing. Today the German school is headed by Karl Heinz Priese. The French, thanks to Jean Leclant, have compiled since 1960 in the Meroitic Epigraphic List (Répertoire d'épigraphie méroitique) several thousands of texts. In the III Century before our era, the 'Island of Meroe' acquires a complete and distinct identity with political ramifications reaching as far as Egypt. The 'Island' entertains with the kings in Alexandria privileged relations both on the economic plane and on the cultural. Under Ptolemy II Philadelphus two new ports are created on the Red Sea, named after his mother Berenice and located at the exits of the caravan routes. The site of Soterial-Limen, the present day Port Sudan, allows access to the 'Island of Meroe' through the Nile or the Atbara river. Further south, Ptolemais-of-the-hunts is a great centre for the collection of ivory and living elephants, Ptolemy II having plans to use them in combat. Finally, Ptolemy III Evergetes creates in the extreme south the port of Adulis. The exploitation of the gold mines enriches the two parties. The tradition has it that the king Arkamani I received a Greek education from the multitude of Alexandrine litterati working at the Meroe court. At the beginning of our era, the Meroitic kingdom is at its peak. In 23 BC its troops attack the towns of Elephantine and Aswan. The Roman response is not long in coming and Pliny the Elder relates the expedition led by the prefect of Egypt, Caius Petronius. The Meroites were defeated at Dakka and the fortress of Qasr Ibrim was taken. Did the Roman troops reach as far as Napata? The peace was signed in 21-20 BC and the border was fixed at Maharraqa, in Lower Nubia. The peace concluded with Rome allowed the kingdom to develop and evolve, but the conquest of Dacia (Rumania) by Trajan, whose gold mines are easier of access than those of Nubia, generated a commercial network from which the kingdom of Meroe would gradually be excluded. In 298, the emperor Diocletian relocates the border to Aswan following the raids of the Blemmyes who, together with the Noba, occupied Lower Nubia. In the middle of the IV Century AD, the Abyssinian king Ezana led a campaign as far as the mouth of the Atbara river, having fought the Meroites with the aid of the Blemmyes and the Noba. The disappearance of the great kingdom has many probable causes: the arrival of peoples coming from Darfur and Kordofan, who are thought to have created a capital at Alwa, near Khartoum, problems with the succession within the royal family and the predominance of the Noba, with as a backdrop an increasingly manifest desertification between the Sixth and Fifth Cataracts. However, if the Meroitic kingdom disintegrated into small principalities, its civilisation lasted until the emergence of Christianity, that is to say until around the VI Century of our era. Within this time we need to include a period called the post-Meroitic (between the IV and VI Centuries) which revived the traditions of the Neolithic and of the Kerma culture, with large tumuli and ritual funerary sacrifices. Ancestral customs return to the fore.

For more information, consult the book of Joy Soule-Nan, 'La Nubie des Pyramides'

EPILOGUE The post-Meroitic episode brought to a close the destiny of the Land of the Cataracts, and seals several millennia of history. Nubia, a term that over the centuries has come to be applied to a territory extending from Kubaniah to just downriver from the Fifth Cataract, is characterised by its position at the entrance and exit from the African 'corridor'. It held the key to trade and in particular to the products indispensable to the functioning of ancient Egypt. It was an obligatory part of the route on both a geopolitical and cultural levels. Today, only traces remain, witnesses of the beliefs of another age. As Jean Leclant has written of this magnificent land, 'On the banks of a grandiose river, in the silence of near solitude, there is every morning the fascinating spectacle of the birth of the world before man came to destroy it through his modern inventions'. |

|