|

KERMA

Since the most remote antiquity, the capital of the kingdom of Kerma, located upriver from the Third Cataract, benefits from an exceptional location: - It is protected from the Egyptian incursions by the Great Cataract (the second). - It develops in a rich basin watered by a fluvial network of which the ancient Wadi el-Khowi is part. Geomorphological studies have confirmed that in the third Millennium islands of various sizes created environments favourable to life. South and west of the Letti basin the 1000 kilometers of the Wadi Howar is an even greater economic player, connecting the Kerma basin with the heart of Africa. This function of the Wadi Howar is replicated by the Wadi el-Melik. - At the confluence of the routes connecting Egypt to Nubia, to the west, through the Libyan oasis, and to the east, in the direction of the Red Sea, Kerma controls the gold mines around the Third and Fourth Cataracts. - It holds the key to the exchanges of products brought by the caravans coming from Darfur and Kordofan (to the south-west) and the land of Punt (to the south-east). All these advantages confirm the power of the kingdom of Kerma, probably called Yam and/or Kush by the ancient Egyptians. Since 1986, the eponymous capital of the kingdom of Kerma has been studied by the archaeological mission of the University of Geneva. Charles Bonnet was its director over some thirty years. Through his work that continued the excavations of the American George Reisner, he has allowed us to better understand the remains of the royal city, of the cemetery and of the site of Dokki Gel.

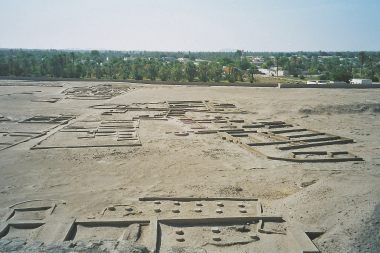

The Royal City During the III and II millennia BC the capital extends over some twenty hectares to the east of the Nile. To the north-east there are religious buildings and a palace of Meroitic date. To the south-west, there is a temple and an administrative centre built during the Kerma Classique (ca. 1750-1550 BC). It includes a harbour area today within the modern town. Two cemeteries, beginning in the Egyptian New Kingdom (ca. 1550-1050 BC) and stretching as far as the Christian era, surround the agglomeration to the north and the south. One estimates these urban areas to cover about fifty hectares.

|

Access to the main temple of the royal city of Kerma / Abords du temple divin de la cité royale de Kerma

Main temple of the royal city of Kerma : solid mass made of raw bricks / Temple divin de la cité royale de Kerma : massif plein en brique crue

Probable vestiges of administrative or religious builings in the royal city of Kerma / Arasements de bâtiments probablement à usage administratif ou religieux dans la cité royale de Kerma

Vestiges of administrative buildings, with the trace on the ground of a hut used for meetings / Arasements de bâtiments à usage administratif dont le plan au sol d'une hutte servant probablement à des réunions

Hut for administrative meetings in the royal city of Kerma / Hutte à usage administratif de la cité royale de Kerma

Vestiges of the façade of the main temple in the royal city of Kerma reminding the pylon of the egyptian temple / Vestiges de la façade du temple divin de la cité royale de Kerma rappelant le pylône du sanctuaire égyptien

Steps going to the terrace of the main temple with a full mass of raw bricks as inner structure / Montée vers la terrasse du temple divin dont la structure interne est un massif de briques crues

On the way to the old cemetery of Kerma / Sur le chemin de la nécropole de l'antique Kerma

Funeral temple of the old cemetery of Kerma / Temple funéraire de l'antique nécropole de Kerma

Entrance of the funeral temple (called deffufa by the local people) in the cemetery of Kerma / Entrée du temple funéraire (appelé deffufa par les locaux) de la nécropole de Kerma

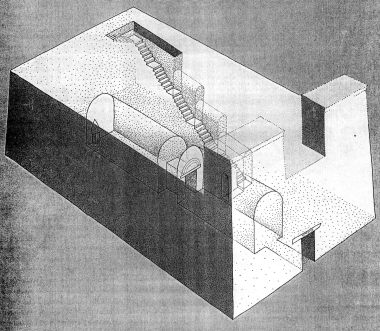

Drawing of the funeral temple in the cemetery of Kerma (Swiss mission Dukki Gel-Kerma) / Dessin reconstituant le temple funéraire de la nécropole de Kerma (Mission suisse Dukki Gel-Kerma)

Graves tumuli in the cemetery of Kerma / Tombes tumuli de la nécropole de Kerma

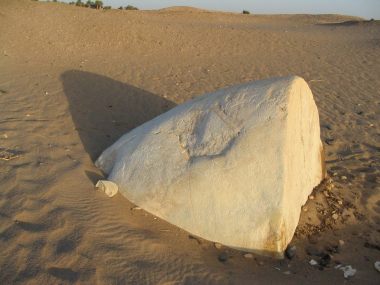

In the cemetery of Kerma, cone usually put on the big tumuli / Cône qui surmontait les grands tumuli de la nécropole de Kerma

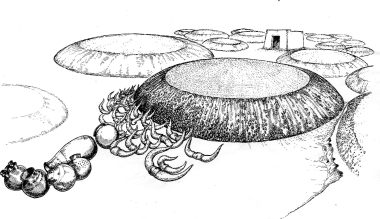

Drawing of the tumuli in the cemetery of Kerma (Swiss mission Dukki Gel-Kerma) / Dessin représentant les tumuli de la nécropole de Kerma (Mission suisse Dukki Gel-Kerma)

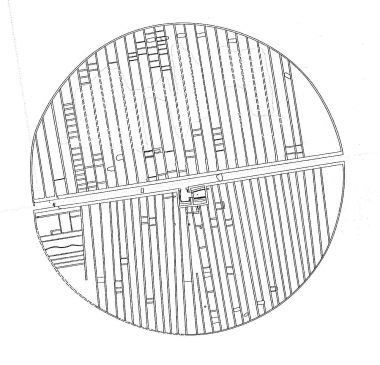

Inner sketch of the great tumuli at the classical period of Kerma (1750-1450 B.C) - Swiss mission Dukki Gel-Kerma / Plan intérieur des grands tumuli de l'époque classique de Kerma (1750-1450 av. J.-C.) - Mission Suisse Dukki Gel Kerma

Bas-relief fragment of the main door of the funeral temple in the cemetery of Kerma representing the egyptian winged disk / Fragment du bas-relief de la porte d'entrée du temple funéraire de la nécropole de Kerma, représentant le disque ailé égyptien

|

|

On the slide show, see drawings by Ch. Bonnet, reconstruction of the chapel C7 (view to North), shematic plan of KII and KIII and the reconstruction of temple KII Throughout antiquity, this metropolis, residence of the kings and dignitaries linked to the royal family, - is surrounded by an enclosure with towers protecting the entrances to the city. - has different quarters. The remains of the most important are the ruins of a Kerma Classique palace, a circular edifice, probably a large hut, and a large structure of mud bricks.

The mud brick structure: identified as the major temple of the town, it is called deffufa by the locals. On inspection, one can see in its general structure, a singular resemblance with Jebel Barkal. There is no court, nor succession of rooms, nor sanctuary, apart from the remains of a pylon. This structure might be thought to reproduce the chthonian world of the residence of Amun of Jebel Barkal. During the excavations, the head of a ram was found, suggesting a cult where this animal was its hypostasis. On the flanks of the structure, one distinguishes the location of different rooms, probably dedicated to secondary deities. In this cult area, the excavations have revealed numerous bread moulds, suggesting the production of offerings.

The Hut: a meeting place, identified as a palace, wherein one notes the traces of some storerooms.

The Palace: built during the Kerma Classique period, it probably included an audience hall, bedrooms, store rooms and large silos. - To the south-west of the town, a secondary agglomeration was protected by powerful fortifications, some of which were dug as far as seven metres deep into the ground. It is possible to make out two large rooms and a series of chapels, but the purpose of this complex is unclear. As it develops, the city is surrounded by walls, bastions and deep ditches.

The cemetery The cemetery is located on what was once an island during the Pre-Kerma period (ca. 3000-2400 BC). From the middle of the III Millennium, this area became increasingly arid and the capital moved towards the Nile. During the great historical phases studied by Brigitte Gratien, Kerma Ancien (ca. 2400-2050 BC), Kerma Moyen (2050-1750) and Kerma Classique (1750-1450), the tumuli became increasingly important. They can reach up to 100 m in diameter towards the middle of the II Millennium. They are made up of a funerary chamber that adjoins a central corridor, onto which open secondary corridors. The excavations of Reisner have revealed the presence of humans 'sacrificed' accompanying the deceased ruler, who could be a man, a woman or an adolescent. In one of the great tumuli, the archaeologist unearthed 400 human skeletons. In many civilisations, ritual killing was practiced, and up to the beginning of the III Millennium, Egypt followed this practice. The reasons were without doubt both religious and political. The Hymns of the Pyramids of ancient Egypt state that, at his death, the king becomes a star, whose light would have benefited his entourage in the after life during the Kerma Classique. We may also suppose that for reasons of political stability it was desirable to protect the newly elected sovereign from assassination or attempts to usurp his power, by introducing this rite on a large scale. Unfortunately, there is also a demographic effect, which the Egyptian invader at the beginning of the New Kingdom takes advantage of. In the modern town, Charles Bonnet has found in the course of his excavations a royal tomb, later in date than the tumuli, that had the form of a large well. There was no evidence of skeletons from 'sacrifices', but traces of a deliberate fire that may be attributed to the Egyptians.

On the slide show, see drawings by Ch. Bonnet, reconstruction of the chapel C7 (view to North), shematic plan of KII and KIII and the reconstruction of temple KII

|

|