|

UNESCO CAMPAIGN - 1960 TO 1972 The river has always posed problems, and since Antiquity the Egyptians have had to face up to the inconsistencies of its water yield. To learn more, click here (annexe 1)

The mastering of the drought and the sharing of the flood waters are part of the royal responsibilities. In Egypt, the river does not have a significant gradient, and it is in Nubia that the lie of the land moves the flood waters along. The flow (number of cubic metres by second) is linked to the rains in the Ethiopian highlands, located at 1800 metres of altitude. This change in level, together with the cataracts, influences the speed of the current. It has made it possible for the flood to cross the Nubian Deserts and to speed up the arrival of 'the new water', source of life. To learn more, click here (annexe 2) At the beginning of the 19th Century, industrial development together with a quickly growing population demands a higher yield from the river. Muhammad Ali has the ancient canals in the delta re-excavated and enlarged. In 1835, he orders the construction of a dam to the north of Cairo that is completed in 1890, the dammed waters being used to irrigate fields all year round.In 1902 a dam at Asyut feeds Middle Egypt. In 1909, those of Nag Hammadi and of Esna allow the development of Upper Egypt.

However, the building of the first Aswan dam upsets the millenary irrigation methods. Built from the plans of the British engineer Wilcock, it reduces the risk of the too feeble floods. The lake created by this construction inundated Nubia as far as Wadi es-Sebua, at 160 km to the south of Aswan. It allowed for the yearly removal of sludge. The economic and demographic developments requires it to be raised twice: initially by 5 metres (between 1907 and 1912), later by 4 more metres (between 1929 and 1934), creating a water reserve reaching as far as Wadi Halfa, on the Egyptian-Sudanese border. In 1961, the lack of equilibrium between the demographic expansion and the food resources forces the country to import food supplies for the first time. |

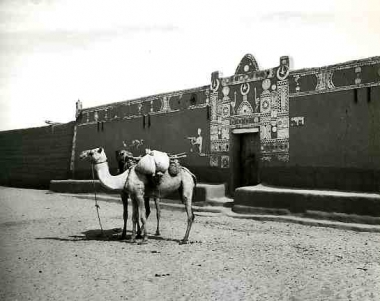

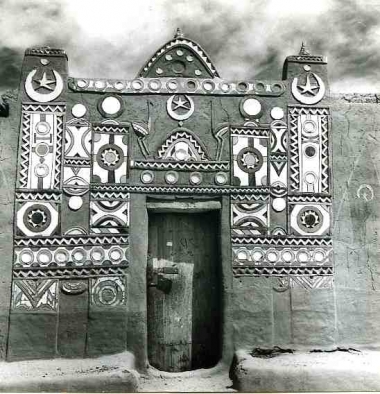

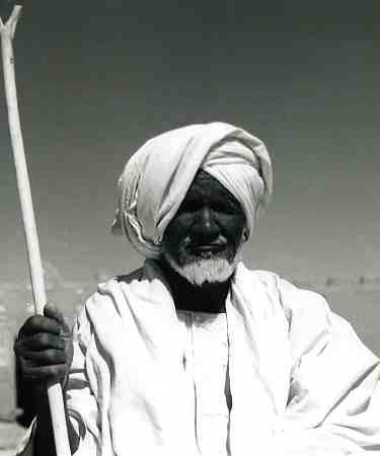

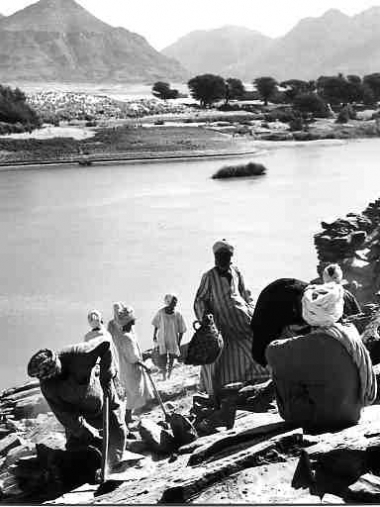

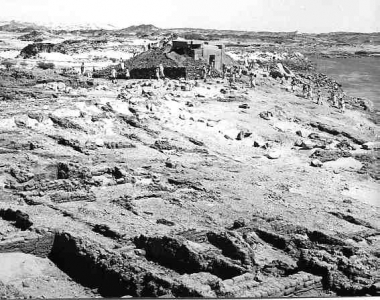

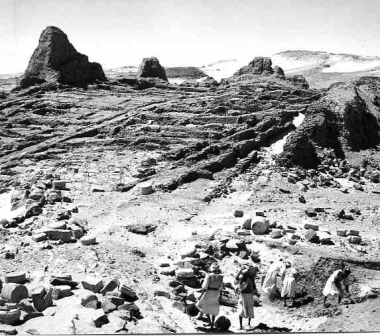

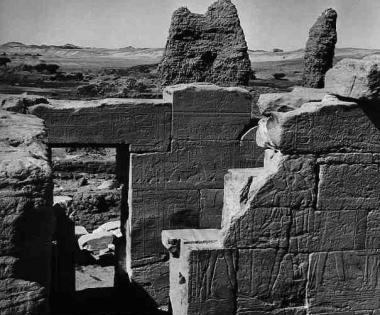

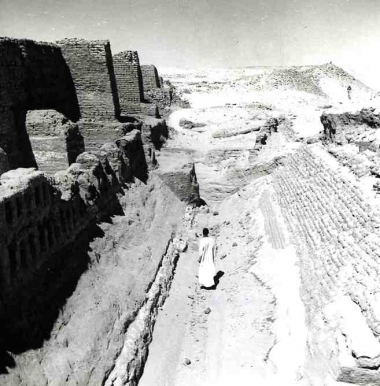

Small aircraft called "love" used for archaeological survey in sudanese Nubia (photo Unesco/Rex Keating 1960) / Le petit avion appelé "Love" qui servit aux repérages archéologiques en Nubie soudanaise (photo Unesco/Rex Keating 1960) Beautiful Nubian house with decorated entrance at Ashkeit. Today, except this portal decoration, we can still observe large houses between Kawa and Nubia Lake (photo Unesco/Rex Keating 1960) / Belle maison nubienne à l'entrée très décorée. Aujoud'hui, excepté ces décorations, on peut encore observer ces importants habitats entre Kawa et le lac Nubia (photo Unesco/Rex Keating 1960) Typical portal decoration which contained many symbols having their roots in ancient traditions and beliefs (photo Unesco/Rex Keating 1960) / Décoration typique de l'entrée d'une maison nubienne affichant de nombreux symboles dont l'origine remonte aux anciennes traditions et croyances (photo Unesco/Rex Keating 1960) Near Abka, Second Cataract, a Nubian who refused to leave his land (photo Unesco/Rex Keating 1966) / Près d'Abka, Seconde Cataracte, un Nubien refusant de quitter sa terre natale (photo Unesco/Rex Keating 1966) At Ukma, every one try to save his history but can do nothing about the beautiful landscape (photo Unesco/Rex Keating 1960) / A Ukma, chacun essaie de sauver l'histoire nubienne mais ne peut rien faire en ce qui concerne le paysage (photo Unesco/Rex Keating 1960) Seen from the aircraft, the southern end of the "Stone Belly" or Batn el-Haggar. We can see some arrows showing on the left bank, the fortresses of Semna south and Semna west and on the right bank, Kumma (photo Unesco/Rex Keating) / Vue aérienne de l'extrémité sud du "Ventre de Pierre" ou Batn el-Haggar. On peut discerner les flèches montrant sur la rive gauche les forts de Semna sud et de Semna ouest et sur la rive droite, Koumma (photo Unesco/Rex Keating) Granitic barrier situated at the level of the fortresses of Semna west and Kumma. The researches of J. Vercoutter were going in the way that a dam should have been built during the Middle Empire under the king Amenemhat III. At the bottom, ruins of the fortress of Kumma (photo Unesco/R. Keating 1964) / Barrière rocheuse située au niveau des forteresses de Semna ouest et de Koumma. Les recherches de J. Vercoutter l'ont amené à penser que cette barrière de granit avait pu servir de base pour construire, sous le roi Amenemhat III, une espère de barrage. Au fond, vestiges de la forteresse de Koumma (photo Unesco/R. Keating 1964) Inside the fortress of Semna west, the dismantling of the temple of Khnoum (photo Unesco/Rex Keating 1964) / A l'intérieur de la forteresse de Semna ouest, travaux de démantelèment du temple de Khnoum (photo Rex Keating 1964) General view of the Semna west fortress (photo Unesco/Rex Keating 1964) / Vue générale de la forteresse de Semna ouest (photo Unesco/Rex Keating 1964) Khnoum temple of the fortress of Semna west (photo Rex Keating 1964) / Le temple de Khnoum de la forteresse de Semna ouest (photo Rex Keating 1964) Inside rooms of the temple dedicated to the god Khnoum and the king Sesostris III, built under Thotmes III (1504-1450 BC). Today, this temple is in the Museum of Khartoum (photo Unesco/Paul Almasy) / Salles intérieures du temple dédié à Khoum et au roi Sésostris III construit sous Thotmès III (1504-1450 BC). Aujourd'hui, ce temple est dans le Musée de Khartoum (photo Unesco/Paul Almasy) Dismantling of the temple of Khnoum of the fortress of Semna west (photo Unesco/Rex Keating 1964) / Démentèlement du temple de Khnoum de la forteresse de Semna ouest (photo Unesco/Rex Keating 1964) Under the direction of Dr. Friedrich Hinkel and with very poor means, the workmen use probably the same technics for moving stones that during Antiquity (photo Unesco/Rex Keating 1964) / Sous la direction du Dr. Friedrich Hinkel et avec très peu de moyens, les ouvriers utilisent probablement les mêmes techniques pour le transport des pierres que dans l'Antiquté (photo Unesco/Rex Keating 1964) Always the same old technics and means under the direction of the German architect, Dr. Friedrich Hinkel /Toujours les mêmes vieilles techniques (travaux dirigés par l'architecte allemand, Dr Friedrich Hinkel All over, desert and poor means for railway... (photo Unesco/Rex Keating 1964) / Partout le désert et de pauvres moyens pour construire des rails afin d'acheminer les blocs de pierre (photo Unesco/Rex Keating 1964) Unexpected and genious railway for the transportation of the stones (photo Unesco/Rex Keating 1964) / Voie ferrée de génie pour le transport des blocs de pierre du temple de Khnoum (photo Unesco/Rex Keating 1964) The Unesco Radio and Television Expedition led here by Rex Keating, descending from the temple of Khnoum to the river along one of the main streets of the fortress of Semna west (photo Unesco/Rex Keating 1960) / La Radio et la Télévision de l'Unesco conduite ici par Rex Keating qui descend du temple de Khnoum vers le fleuve le long d'une des rues principales de la forteresse de Semna ouest (photo Unesco/Rex Keating 1960) Remains of the Semna village which, about 2000 BC, marked Egypt's southern frontier. Here it is slowly submerged by the upstream lake of Nubia (Lac Nasser) (photo Unesco/Rex Keating) / Ce qui reste du village de Semna, qui fut aux environs de 2000 av. J.-C. la frontière sud de l'Egypte. Ici, il est peu à peu submergé par les eaux de retenue du lac Nubia (Nasser) (photo Unesco/Rex Keating) Bases of the XIIe egyptian dynasty temple in the fortress of Kumma (photo Unesco/Rex Keating) / Arasements du temple édifié sous la XIIe dynastie égyptienne de la forteresse de Koumma (photo Unesco/Rex Keating) Looking south the cataract, the main fortified gateway of the fortress of Shelfak which was situated on the left bank of the Nile (photo Unesco/Rex Keating 1960) / Depuis le sud de la cataracte, entrée défensive de la forteresse de Shelkak qui était située sur la rive gauche du Nil (photo Unesco/Rex Keating 1960) The fortress of Askut built on an island in the middle of the Second Cataract (photo Unesco/Rex Keating 1964) / La forteresse d'Askut construite sur une île au milieu de la Seconde Cataracte (photo Unesco/Rex Keating 1964) Inside the wall of the fortress of Serra east, ruins of an early Christian church (photo Unesco/Rex Keating 1960) / A l'intérieur du mur d'enceinte de la forteresse de Serra ouest, ruines d'une église primitive chrétienne (photo Unesco/Rex Keating 1960) Mirgissa fortress with buildings for the egyptian administration. A small temple was dedicated to Hathor, the deity of Iken. A very long pathway separated those places from the first fortified fortress wall (photo Jean Vercoutter) / La forteresse de Mirgissa avec des bâtiments destinés à l'administration égyptienne. Un petit temple était dédié à Hathor maîtresse d'Iken. Un long couloir séparait cette organisation politique et religieuse du premier mur d'enceinte (photo Jean Vercoutter) This gateway facing north, allowed to go toward the first wall through a very massive door with bastions making a very narrow way blocked if necessary by two wooden doors and an herse (photo Unesco/Rex Keating - text Francis Geus) / On entrait dans la forteresse par le nord, en franchissant le premier mur par une porte massive à bastions enserrant un étroit passage que pouvaient bloquer deux portes en bois et une herse (photo Unesco/Rex Keating - texte Francis Geus) About fifty workmen take out the sand between the inside wall and the exterior one of the Mirgissa fortress. This last looks like a dune parallel to the visible wall. Both were 10 m high and 6 m wide with squared bastions and angle towers (photo Jean Vercoutter) / Environ 50 ouvriers travaillent au dégagement du fossé séparant les deux murs d'enceinte de la forteresse de Mirgissa. Ce qui semble être une dune parallèle au mur de brique crue est en réalité l'emplacement du mur extérieur. Tous les deux mesuraient 10 m de haut et 6 m de large avec des bastions carrés et des tours d'angles (photo Jean Vercoutter)

Jean Vercoutter and his egyptien raïs talking about excavation work (photo Jean Vercoutter) /Jean Vercoutter et son contremaître egyptien parlant de l'avancement des travaux de dégagement (photo Jean Vercoutter) Mirgissa site was extended over three km and the fortress has been evaluated at 4 hectares. From the fortress, a big wall of 600 m was protecting a large city (about 7 hectares). Towards the north-east, another city, not fortified, was build near a small fortress watching a branch of the Nile just facing the Dabenarti fortress also on an island (photo Unesco/Rex Keating) / Le site de Mirgissa était étendu sur 3 km et la forteresse a été évaluée à 4 hectares. Depuis la forteresse, un grand mur de 600 m protégeait une ville d'environ 7 hectares. Vers le nord-est, une autre ville non fortifiée était construite près d'une petite forteresse qui surveillait un bras du Nil juste en face de la forteresse de Dabenarti édifiée sur un ilôt de la Seconde Cataracte. Sliding pathway, connecting the natural harbour and a small city at 2 km downstream. This road made of mud and wooden logs allowed to pull up the boats or the goods in order to avoid the rapids of the Second Caratact (photo Jean Vercoutter) / Glissière reliant le port naturel à une localité située à plus de 2 km en aval. Cette route de limon armée de rondins de bois permettait de tracter des bateaux ou des cargaisons afin d'éviter le franchissement des rapides (photo Jean Vercoutter) The huge fortified wall of Buhen fortress made if mud bricks (photo Unesco/Rex Keating 1960) / Mur d'enceinte de la forteresse de Bouhen fait de briques crues (photo Unesco/Rex Keating 1960)

Earlier excavations of the western fortifications of Buhen fortress showing bastions, arrow slits, ramparts, inner ditch (photo Unesco/Rex Keating 1960) / Fouilles anciennes de la partie ouest de la forteresse de Bouhen montrant les bastions, les meurtrières, les remparts, le fossé intérieur (photo Unesco/Rex Keating 1960) Excavation work in progress at the fortress of Buhen. Like all the fortresses of the Second Cataract, Buhen will be submerged by the lake of the new Aswan dam (photo Unesco/Rex Keating 1960) / Travaux de dégagement de la forteresse de Bouhen. Comme toutes les forteresses de la Seconde Cataracte, Bouhen sera immergée par les eaux du lac de retenue du Haut Barrage d'Assouan (photo Unesco/Rex Keating 1960) The old Wadi Halfa town was on the east bank of the Nile, a few miles from the egyptian frontier. It has been submerged under 40 m of water (photo J. Stordy) / La ville ancienne de Ouadi Halfa qui était située sur la rive est du Nil, à quelques kilomètres de la frontière égytienne. Elle a disparue sous environ 40 m d'eau (photo J. Stordy) The former and pleasant Nile Hotel at Wadi Halfa is now under the water (photo Unesco/ Rex Keating 1960) / L'ancien et charmant Hôtel du Nil à Ouadi Halfa est maintenant sous les eaux (photo Unesco/Rex Keating 1960) In the foreground, the second site under excavation of Faras south, showing foundations of the Middle Kingdom temple. The mound in the background, which has yet to be excavated, is surmonted by a Dervish fortress and the ruins of an early christian church (photo Rex Keating 1960) / Au premier plan, le second site en cours d'exploitation de Faras sud, montre les fondations du temple du Moyen Empire. Le monticule à l'arrière-plan est encore à explorer. Il est surmonté d'une forteresse derviche et de ruines d'une église chrétienne (photo Rex Keating 1960) At Faras, the grave of Bishop Joannes (photo Rex Keating 1960) / A Faras, la tombe de l'évêque Jean (photo Rex Keating 1960) At Faras east, ruins of an early christian church (photo Unesco/Rex Keating 1960) / A Faras Est, ruines d'une église chrétienne primitive (photo Unesco/Rex Keating 1960)

Member of the polish expedition uncovering the top of a coloured fresco in the great early christian church at Faras (photo Unesco/Rex Keating 1962) / Un membre de l'expédition polonaise met à nu une fresque polychrome d'une église des premiers temps de l'ère chrétienne découverte à Faras (photo Unesco/Rex Keating 1962) The columns of the Faras cathedral, now in the courtyard of the archaeological museum of Khartoum (photo Rex Keating 1960) / Les colonnes de la cathédrale de Faras maintenant dressées dans l'enceinte du musée archéologique de Khartoum (photo Rex Keating 1960)

|

| Domestic agricultural produce is no longer sufficient for local needs, and there is an increasing need for industrialisation: these are the reasons for one of the great projects of Nasser's revolution in 1952. Two years later, an international committee of experts pronounces in favour of a dam, a project which the government adopts. The Sadd el-Ali or 'High Dam' is built 7 kilometres above the first dam: it measures 3.6 kilometres in length, 980 metres wide at its base, and 40 metres in height. During five years, day and night, 30 000 men work on its construction.

Reference has frequently been made to the advantages and disadvantaged of the High Dam on the Nubian and Egyptian territories. One factor must be highlighted, the movements of substructure and of subsidence in relation to the tectonic plates. They threaten the fertile land of the delta that were filled and kept above water thanks to the annual deposition of silt. To learn more, click here (annexe 4) Since 1964, this extraordinary cement is no longer supplied to achieve the natural warping that gave the river banks in the North their perfect homogeneity. The construction of the High Dam has submerged the Nubian lands under approximately 60 to 70 metres of water. Was there another solution? In December 1955, an alternative, 'The Nile Waters Question' was proposed by the Sudanese government in response to the 'Report on the Monuments to be Submerged by the Sadd el-Ali' compiled by the archaeologists and Egyptian experts who had visited the sites between Aswan and Wadi Halfa. Contrary to the Egyptian project, the Sudanese proposal envisaged a programme of global development from the mashes of the Sadd (southern Sudan) as far as the delta (northern Egypt). It was based on the kind of development achieved in the Tennessee valley (United States), with a series of small dams that would have drained the waters of the great lakes and those from the Ethiopian rains. Egypt and Sudan were to be joint beneficiaries. To learn more, click here (annexe 5)

If the project had gone ahead, all of Lower Nubia would have been saved. In Sudan, the building of the High Dam would flood 200 kilometres of territory, from Adindan to the Dal Cataract as well as the 300 archaeological sites inventoried. To learn more, click here (annexe 6)

When Jean Vercoutter accepted the post of Director of the Department of Antiquities in Khartoum, in 1955, he is at once concerned by the threatened heritage. Some months after his appointment, he submits to president El-Azari a ‘Preliminary Report on the Sudanese monuments and the Sites liable to be submerged'. The president, an affable and courteous man, reassured the archaeologist: ‘Do not worry, Sudan will never accept the construction of the new Aswan dam.' Unfortunately, a few months later, the head of state is replaced by the general Ibrahim Abbud who gave his agreement to Nasser. In defence of the latter, and according to Jean Vercoutter, ‘This man from the east had never visited Wadi Halfa and did not have the least idea of the importance of northern Sudan.' In Egypt, the temples of Lower Nubia were regrouped into the ‘natural oases' of Kalabsha, Wadi es-Sebua and Amada, those of Abu Simbel were raised and that of Philae was moved. What happened to the men and women that abandoned their motherland in 1963 and 1964? In Egypt, they were divided between 44 new villages placed in the shape of a horseshoe between Luxor and Aswan. In Sudan, they where resettled at Khashm el-Girba in the province of Kassala, in an environment and with living conditions to which they were not accustomed. To learn more, click here (annexe 7)

Hassan Daffalah, the Egyptian commissioner for the district of Wadi Halfa during the UNESCO campaign, has spoken of this people, full of generosity and courtesy: ‘The Nubians were renowned for their honesty and their love of peace.... Modern society has a lot to learn from these attitudes towards life...' It is also necessary to render homage to Rex Keating (1910-2005), who was director of the Mission Radio and Television of UNESCO from 1956 to 1971, during the Third campaign to safeguard the Nubian temples. After studies in London, his career as a member of the press took him to the Eastern Mediterranean basin. He was the founder of the European service of the radio broadcasting service in Cairo, that he ran from 1935 to 1945 (he was later director general of the radio broadcasting service in Palestine, and then on Cyprus. In 1972, 1973 and 1980, he was consultant for UNESCO and made films in West Africa for sanitary and agricultural development.

To read the speach of Vittorino Veronese, clik here To access Rex Keating 's web site, click here

|

|